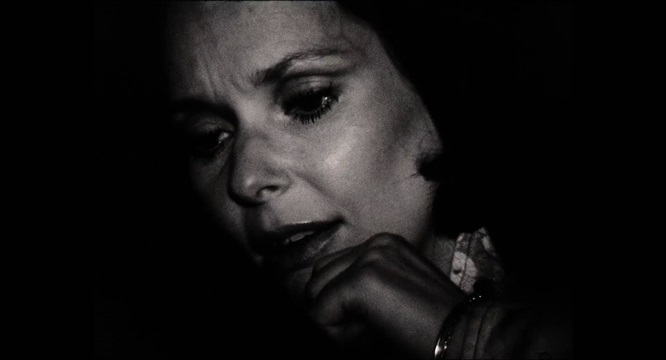

:: Julie Rich (Susan Strasberg, "the critic lady") in The Other Side of the Wind (Orson Welles, 2018) [Netflix]

– What happened to the critic lady?

– She’ll live.

– Yeah, she’ll live to write about it.

This exchange occurs near the end of Orson Welles’s mesmerising film The Other Side of the Wind. Among its many secondary characters is a Pauline Kael-like figure; she is sharp, alone, looking for answers. She displays keen interest in the work of aging director Jake Hannaford (a Wellesian type played by John Huston), but traffics in none of the adulation that oozes from the gaggle of boy critics also present at the filmmaker’s birthday party. Hannaford and his entourage refer to her as “the critic lady.” To them, she is a nuisance, a hag, a killjoy. Questioning the old man’s sexuality, she provokes him so much that he slaps her in the face. The younger director Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich essentially playing himself) asks what happened to her, only to then take one last dig. In this world of heroic cinephilia, the critic lady — the lady critic — is a problem.

The boys come in for none of the vitriol directed at the critic lady. The Other Side of the Wind delights in a masculinist ideal of filmic creation and community, and understands film criticism similarly. In this, it is not an outlier: in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, David Bordwell praises Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler for their “virility” and “bravado,” and shows how these men laid the foundation stones of film criticism as it continues to be practised today. Bordwell celebrates Ferguson for writing as if he were “set[ting] out to disprove New Yorker editor Harold Ross’s claim that movie reviewing was for ‘women and fairies.’” [1]

Ross’s patronising remark succeeds in signalling the lack of intellectual seriousness he attributed to film criticism as strongly as it fails to accurately describe the demographics of the activity. If only women and queers had taken over the film pages of publications everywhere beginning in the 1940s! Film history would look different. But neither then nor now have such voices enjoyed a fair presence. Not enough virility and bravado, maybe. The rhetorical flourishes of “the Rhapsodes” may have waned, but a sensibility persists — one that convinced me for many years that I had no place in film criticism.

When critics ruminate on the health or history of their field, its exclusions are thrown into stark relief. Sight & Sound’s October 2008 feature “Who Needs Critics?” invited twenty-one reflections from twenty-one men, twenty-two if you count editor Nick James’s introduction. That same year, Cineaste’s critical symposium “Film Criticism in the Age of the Internet” comprised twenty-three contributions, nineteen from men. Unsurprisingly, these examples are also marked by a blinding whiteness and a paucity of queer perspectives.

But let’s return to that exchange from The Other Side of the Wind. No attentive viewer will miss the many hints of ambivalence and auto-critique that pepper the film. Welles indulges the priapic myths of Hollywood old and new, while also gesturing to the pathetic, swollen vanity of the male auteurs at its centre. The Kael character is played as an unsympathetic virago, surely, but there is no denying that her insights into Hannaford’s practice are easily the most acute. It might not be entirely against the spirit of the film, then, to twist Otterlake’s words and see in this scene, in the Kael character, a resilient figuration of what it is to be a woman who cares, and writes, about cinema. She is pushed around, insulted, not taken seriously, on the edges of a boys’ club — yet she is still there, still writing, living for it.

She is — we are — still here, still writing, and things are changing. Ten years on from the embarrassments at Sight & Sound and Cineaste, think-pieces and panels on the status of film criticism are more likely to consider the underrepresentation of historically marginalised groups than they are to engage in still more hand-wringing about the impact of the internet. Increasingly, finally, there is a widespread recognition that greater inclusivity is imperative. It is not merely about fulfilling quotas; it affects what gets written, which films are championed, which films are critiqued, and how.

Yet privilege is not something given up easily, and the backlash against the new visibility of writing by women and people of colour is already here. In “Film Criticism’s Identity Crisis”, published in The American Conservative, we learn that “TV and film criticism is now dominated by writers who view their role as policemen [sic] of diversity and expositors of social justice issues”. [2] Or, take this bitter entry from the 2017 Sight & Sound year-end poll:

Imagine if films were reducible to information, untethered from aesthetics and the emotional, sensory experience of watching them? For some, of course, they are: on the whole, 2017 marked another year in which our dime-a-dozen, write-for-buttons, sing-for-supper PC pedants, barely concerned with film form and much less with film history, continued their campaign to terrorise the cinema into providing something resembling a coherent, clear-cut blueprint for a better world. [3]

This statement is brimming with contempt, boiling over with resentment, and its target is clear. The author goes on to complain about “thinkpiece[s] written with the kind of reasoning and haste characteristic of a first-semester undergraduate essay linking the allegations against Harvey Weinstein to matters of onscreen representation of fictional women”, bafflingly deeming them to be evidence of a “reverse McCarthyism” in action. Here we are, on the hunt, ready to ruin your pleasure with our narrow ideological readings. How dare we suggest that what you consider a work of tremendous artistry is in fact retrograde? We obviously care nothing for film form or film history; there can be no other answer for our objections than ignorance. In a time of political emergency, we are clearly misguided in our enthusiasm for works that offer responses, whether critical or reparative, to the catastrophe of the present.

Domination and terrorism: these are strong words. But these are not fringe views. Rather, they mark out the terms of an ongoing debate that pits critics invested in the politics of representation against critics seeking to defend art for art’s sake. This debate is not new: as Bordwell notes, it reared its head in the 1940s, in the conflict between the Rhapsodes and those Farber termed “plot-sociologists”. [4] Yet it is a debate that is happening again, now in relation to race and gender — often implicitly, sometimes explicitly — in books, magazine editorials, reviews, on Twitter, Facebook, and, of course, in conversation.

Let’s examine the protestations against us “PC pedants”. To be sure, there is some weak writing out there. The era of the attention-grabbing hot take has not been kind to nuance. I thought 1970s and 1980s feminist film theory had put to rest forever the trap of ‘positive images’, but apparently not. What art historian Hal Foster has called a “politics of the signified” has severe limitations [5]; the Bechdel test, the nec plus ultra of such approaches, is hardly any measure of progressiveness or quality.

Yet the caricature is unfair, and the logic is faulty. Form matters, but the old Cahiers axiom is true: a tracking shot is a moral affair. Aesthetics and politics are inseparable. Strong criticism by women and people of colour does not disregard artistry; it simply refuses to allow formal virtuosity to serve as an alibi for racism and misogyny. It confronts moral issues without searching for moral purity. It is intersectional, and has a different sense of what counts as ‘niche’, what is ‘relatable’, and what stories matter. It recognises that film history is, to paraphrase Walter Benjamin, an archive of civilisation as much as it is an archive of barbarism. It knows that genius is a myth invented by white men to help themselves, and to torture themselves.

Such positions upset a certain kind of critic not only because a growing concern for inclusivity might take column inches away from him. More fundamentally, the contemporary vitality of minoritarian criticism reframes his values as something less than the only ones, the right ones, as able to be taken for granted as valid. Every film is political, especially those that purport not to be. The same is true of film criticism. The castigation of ‘identity politics’ is an identity politics.

The claim to appreciate a film exclusively on pure merit has always been spurious, for it disavows how thoroughly the very notions of achievement and relevance are shaped by power, generally to the detriment of those who have historically been excluded from the practices and institutions that build canons and criteria. That there are only five films by women out of some 150 titles in the BFI Classics book series is not because women have made no great films. [6] Echoing Lis Rhodes, who asked “Whose history?” we must now query, “Whose classics?” [7] Born in Flames, Sambizanga, Jeanne Dielman, Variety, Daisies, The Ascent, Beau Travail, Dance Girl Dance, Daughters of the Dust, Portrait of Jason: where are they? To appreciate a film’s ‘quality’ with minimal regard for social factors, with minimal awareness of the biases inherent in such a stance — an attitude widely held, even by critics who would never speak of PC pedants — is to blithely inhabit the privilege of a false universalism. The growing prominence of writing on cinema by women and people of colour heralds a reckoning with that falseness.

In The Other Side of the Wind, the lady critic is called “the critic lady” because she is the only one. This gendering marks her out from the boys, but it is also derisory. In other ways, and for different reasons, it happens often today that women’s filmmaking and writing about filmmaking is labelled as such. Qualified. Festivals, sidebars, journals, and articles redress the historic absence of women by claiming a space apart. This is perhaps a necessary corrective, but it also risks continued marginalisation. In June 2018, Sight & Sound atoned for their 2008 gaffe by offering “A Pantheon of One’s Own: 25 Female Film Critics Worth Celebrating”. Will these critics ever escape being condemned to the particular? I get the Woolf reference, but shouldn’t we be not in a pantheon of our own, but in the pantheon — one radically transformed by our presence?

Radical transformation is certainly happening in contemporary film criticism, but not always in ways that are positive. The possibility of being a salaried critic has vanished for all but a handful, with freelancing, hobbyism, and precarity now the new normal. In addition to a lack of sufficient remuneration, there is the well-worn refrain that critics no longer have any power, with the PR machine and algorithmic aggregators doing the work of shaping audiences. Is it a coincidence that the field has become increasingly open to a diversity of voices precisely at the moment that its financial viability and cultural prestige have vertiginously declined?

For some, it is easy to be wistful for the good old days — but it’s hard to feel that way when the good old days weren’t good for people like you. Given the inability to entirely remake the present, it merits looking for the small openings it affords. If a certain idea of professional criticism is in crisis, perhaps a bigger space can be cleared for other forms of engagement, forms of writing and publication that push beyond snap judgments, new releases, and, yes, bravado, to expand the possibilities of what film criticism can be.

In her 1982 film Reassemblage, Trinh Minh-ha suggests evading the patriarchal structures of authority and power proper to traditional modes of ethnography by “speaking nearby” instead of “speaking about”. We might do the same in our writing, forging a different sensibility. “Nearby” is closer than “about”, and less pre-determined; it entails proximity without domination, the greatest intimacy. It does not mean loving a film, though it might. I think of two very different texts, coincidentally or not both by women, coincidentally or not both about the same film by a woman: Barbara Loden’s only feature, the exquisite Wanda. I think of Elena Gorfinkel’s “Wanda, Loden, Lodestone” and Nathalie Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden.

Made in 1970, Wanda has long suffered critical neglect. Loden stars as the titular character, a blonde who drops out of family life and drifts through coal country. She is never quite the protagonist of her own story. Wanda’s directionlessness is Gorfinkel’s north star. Her text comprises eighteen chiselled paragraphs, some no more than a sentence long, exploring the film’s great preoccupations: a woman’s exhaustion, a woman’s withdrawal. The writing is deliciously overproof and heady, coursing with energy. Somehow each sentence clings to Wanda and pushes out from it, into a fray of bodies, films, refusals, feminisms — finally asking nothing less than how to live.

Where Gorfinkel distils, Léger dilates. Her book began as an encyclopaedia entry on Wanda but developed into an essayistic work encompassing memoir and fabulation; this origin story, recounted within the text, underlines the unkindness of established formats and frames the book as a search, not just for a woman, but for a form that will do her justice. Its French title, Supplément à la vie de Barbara Loden, captures how Léger explodes the enclosures of biography and film criticism alike, declaring that this book will add something more than has yet been allowed. The subordinate is rescued through an act of creative insubordination.

Poetic, roaming, personal, yet precise and political, these texts are informed by tremendous expertise without ever seeking to spar or one-up. Nuance reigns. Gorfinkel writes that Wanda is a testimony to “all the films by women that have remained unmade, unknown, unseen.” Is it too much to say that these texts, for me, do the same for criticism? Their unorthodox excellence and wilful divergence from norms push me to consider the unwritten, the unread. Ross’s remark about film criticism being for “women and fairies” wasn’t true in his time. Perhaps it can be in ours.

:: Barbara Loden in Wanda (1970) [The Criterion Collection]

[1] David Bordwell, The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 37.

[2] Orrin Konheim, “Film Criticism’s Identity Crisis”, The American Conservative (April 28, 2017),

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/film-criticisms-identity-crisis/.

[3] Paul McManus, Rob Philp, Nick Bradshaw and Isabel Stevens, “The best films of 2017 – all the votes”, Sight & Sound (December 2017), http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/best-films-2017-all-the-votes/#/?.

[4] Bordwell, The Rhapsodes, 77.

[5] Hal Foster, quoted in: Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Silvia Kolbowski, Miwon Kwon, and Benjamin Buchloh, “The Politics of the Signifier: A Conversation on the Whitney Biennial”, October 66 (Autumn 1993), 3.

[6] Since the original publication of this essay, further titles by women directors have appeared in the series, including one devoted to Jeanne Dielman.

[7] Lis Rhodes, “Whose History?” Telling Invents Told, ed. María Palacios Cruz (London: The Visible Press, 2019), 48–54.

*

Erika Balsom’s writing on film and art appears in publications including Artforum, Art-Agenda, Frieze, and Sight & Sound. She is a senior lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College London.

This piece first appeared in Koschke, published by Woche der Kritik (Berlin Critics’ Week) in February, 2019.

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |