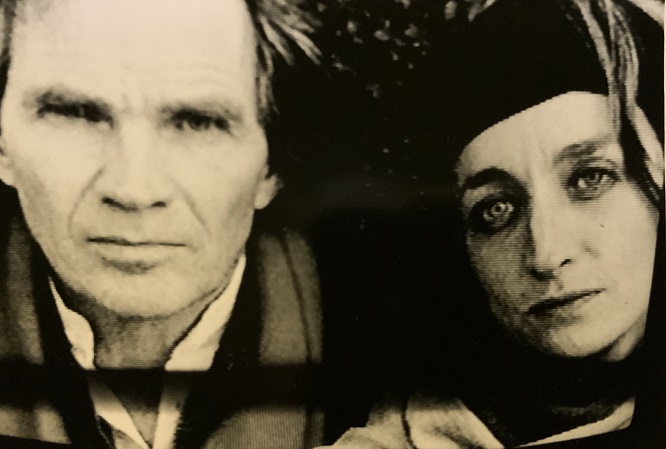

:: David Rimmer, Sarah Butterfield, and their son Milo Butterfield

He had a mane of lion’s hair and the kind of blue eyes that melted walls if he looked at them too hard. West Coast counter-culture was home. He palled up with artists and draft dodgers to create an alternative universe in the wilderness of Storm Bay, dedicated to sailing hand-made boats, lifestyle experiments and ecology. Back in the city, Intermedia was a big tent art alternative that was invited to turn the Vancouver Art Gallery into a hippie playground once a month. David would run 16 mm film loops all night, learning to see the small lives that lay hidden in the frames, and he turned that careful attention into a suite of shorts that played around the world. He moved to New York and set his camera up in the window where it never moved, squeezing out a few seconds of film at a time, over months, creating a neighbourhood portrait, and a new way of seeing. He repeated the trick back in Vancouver, overlooking the train tracks and mountains. Made a masterpiece portrait of his pal Al Neil, the hard drinking loner and jazz iconoclast. David was a loner who liked to be around people. A teacher that never talked. Was there a female student he met across the decades that he didn’t try to bed? In the 80s, he reinvented himself again, finding new ways to string his loops together, stepping across the dreaded divide between film and video. He made travel movies in China, Spain, the Pompidou in Paris, jazz clubs in Poland, streeters in Moscow. His life-long love affair with drugs and alcohol eventually caught up with him; in his ineffable fashion, he self-destructed on the 26th of January 2023.

:: David Rimmer

Here are some words by the one who knew David best, his last partner, the forever eloquent Sarah Butterfield. Recorded three weeks after his death:

David was mercurial and complicated like all poets. I had some of our closest friends come over last week to share stories about David, mostly to comfort Milo [his son] who is in a lot of pain. They loved him, but couldn’t understand him really, he was so often far away in his world of invention and abstraction. My mom always said it was like living with a rock. He’d be quiet for four or five days, then suddenly say something no one could argue with, making you realize he’d been cogitating all that time. That was the way he operated and rocks have irreducible feelings.

I think it came from his solitary childhood. His immigrant parents lived in West Vancouver with no technology, no cars or radio, no one ever argued, they were quiet people. He was let loose in the environment. From a very early age he built boats and sailed them. He was at large, wandering the mountains on the north shore. I think it had a huge impact on the way he absorbed the world.

He was consumed by his mind. I animated the world for us, threw parties, made great food, and he loved that. It was easy to dismiss David as shy, but I don’t think he was shy. He was completely mesmerized by something in his head, his own way of looking. It led him to do remarkable things, like going to India and walking for a month by himself. Milo was four when he announced, “I’m going to India.” He often took himself away, he had to, it was part of his processing. He began in Pondicherry and walked all the way down the coast making Padayatra: Walking Meditation (2005). People kept stopping him and saying there are busses, but he said “No, I want to walk.”

David loved the sea, being off land. He had built boats in the past and taught himself to sail. He had to be at sea, if he wasn’t amongst the trees or running. We bought a boat and lived on it for four years, exploring Canada’s West Coast up to Desolation Sound.

:: Sarah Butterfield, David Rimmer, Milo Butterfield on sailboat

Storm Bay was an important landing place for him. The way David explained it to me was that, in his mid-20s, he had come back from hitching around the world. He got fed up reading Ezra Pound and decided he had to find his own poetic expression. He realized he didn’t want to be a mathematician or an economist as he’d been trained either, he was a maverick outlier who was going to break the rules and reassemble things. In the 60s, he met a bunch of artists in Vancouver who were pioneers at places like Intermedia. They were the underworld. A mixture of artists and clever thinkers found a strip of land they bought cheaply together called Storm Bay. They built whimsical houses and spent an enormous amount of time there developing the land. The contract they wrote stated you could live there, but it was a protected space and could never be sold. David made a lot of work there.

In the early 2000s, we went back to build a little house for ourselves. It was very difficult for me and Milo to integrate ourselves into that community. You can’t catch up with the experiences of others. David built this amazing polygonal glass tree house suspended between the trees. We sailed there with Milo to spend some of our summers. It was very remote and beautiful.

:: View out Storm Bay House

He was a great lover of beauty. He was very sexual, very turned on by intimacy and sexuality. He wasn’t always faithful and often took off. He was electric, a great lover. He came from a hippie time that was still quite chauvinist in a way, but he was very delicate about women. He loved women.

David ran six marathons. He loved this landscape and looked at it very deeply in ways I can’t see because I’m not from here. I don’t see the energy of it, but it was essential for him to encounter. When Milo was tiny, we bought a professional, three-wheel push chair. David would push it in front of him, it had wheels that turned in any direction, so he could run with Milo in the landscape. Winter, rain, sleet, he’d pack Milo in there with a few furry animals and take off. They’d run for an hour and then he’d go and teach at Emily Carr University of Art + Design. He did that every day.

Everyone I know who met David as a teacher said it wasn’t what David said, it was the work he showed and the way he worked that made him such a great teacher. His instruction to them was to break the rules, to experiment and work in chaos and see what happened. He taught by example. He was one of the great refreshing lights in the film department at Emily Carr. His way of looking and thinking was impactful on hundreds of people.

:: David Rimmer and Sarah Butterfield

We worked together in our Vancouver studio, sharing an interest in patterns, the rhythm of insistence and poetry. He’d rip film out of the Steenbeck [editing machine] and hold it up to the sky and then chop it in. He worked with incredible intuition and roughness. He would look at what he was cutting in the mirror, he’d stand away from it, smoke a joint, and it would all come together over time. He knew exactly what he was trying to say, but needed to invent a new language to say it. He said he began all his films in the middle and worked out to either end. He had a central hinge, a prevailing image, and would gather material that would take him to the film’s beginning and end.

He was often unsure of whether he “got it” after finishing a film. He would always say: “It’s what I could do at the time.” He always did what he wanted, you could never change his mind. I think it was a kind of autism. He was compounding, collecting and observing the world until it became a kind of black hole that he disappeared into. Eventually he descended into strange and great depths of himself that few could reach. We were trying to live with him, but he was always on his own journey and it was not always easy.

David had an addictive personality. It got us in a lot of trouble at the end of our relationship. He started drinking a great deal and experimenting with acid. He was persuaded by a local psychologist to take acid because it would take him into a trans-personal zone. I think he was very interested in that, it’s probably why he jogged, running himself into a meditative space almost like a trance.

He took a vast amount of acid one day when Milo was about three and disappeared for twelve hours with this psychologist. I think he never came back again. Over the next five or six years, he declined and drank a great deal and developed early onset dementia which robbed him of his voice. I saw him a lot during that time when he had to go into care. His eyes still spoke: they cried, they smiled, they saw. But he couldn’t speak. He was very lonely, puzzled that he’d ended up there. He had a self-destructive element in him that caught up with him in the end. It was a very difficult and painful time.

The last time I saw him. I’d been in Europe and went up to his room in Yaletown House to give him a hug and tell him about times elsewhere. I found him dead. It was unbelievably shocking, no one had forewarned me. He had died an hour before I saw him. He was so absolutely dead, like a felled tree. A disappearance of spirit, epic when you encounter it.

:: Milo Butterfield and David Rimmer pointing

All photographs from the personal archives of Sarah Butterfield.

For a free book that collects writings on and interviews with David Rimmer: https://mikehoolboom.com/?p=15647

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |