[Petit Chaos]

The Movement as Collective Subject

The most beautiful and essential movie I saw in the last three years was Payal Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021). She was a film student at Pune’s Film and Television Institute of India, who wanted to make a science-fiction documentary about love. She reached out to friends so they could explore together the impossible choices facing women of their generation, pressured by the machines of State and family. How did their intimate experiences reveal underlying mechanisms of power? How has caste and class transformed their bodies? Impossible love and transgressive relationship lay at the centre of her hopes as she gathered scenes and interviews, but slowly events overtook her making, and she made a fateful decision. She would change direction.

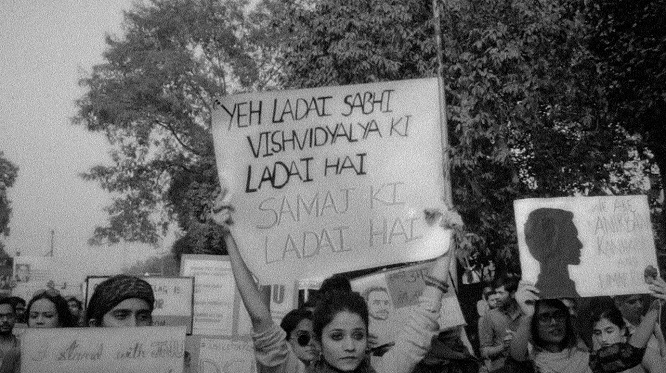

In 2015, she participated in a student strike over the government’s appointment of a right-wing hack to run the school. Narendra Modi’s neoliberal revolution meant a deepening of caste discrimination, an internal war against Islam, along with tuition hikes and privatization. Three years after shooting began, Kapadia graduated, after an endless suite of protests, where she continued gathering material. She had an important chance encounter with filmmaker pal Prateek Vats who, while at his university, had compiled a mountain of footage that he couldn’t find a home for, so he offered it to Kapadia. Slowly, she began gathering moments from universities across the country, alongside news clips, iPhone witnesses, and Super 8 home movie footage. Out of these urgent first-person accounts, the artist began to weave her new love story.

The movie opens with a utopian image. The camera is on the floor, along with a jam of student dancers, their reveries lit up by dancers on the screen behind them. They have turned their cinema into a palace of touch and gesture, brimming with youthful exuberance. It is a scene of liberation, suggesting that the gatherings of art might bring us to this stateless state, where individual expression turns into group joy.

A heartbreaking her and his voice-over lies underneath, tender night voices read letters to each other. When something is missing, language speaks. They are separated by caste and class and parents and the overwhelming fear (usually named “common sense”) the State uses to maintain control. The voice-over provides an anchor for the drift of pictures that ensue, though there are many other voices (no fewer than 23 speakers are named in the credits), along with reporter missives, eyewitness accounts, political speeches, and a clutch of whispered winds that haunt the soundtrack.

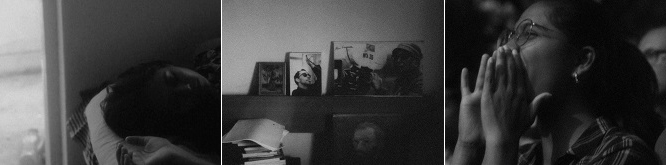

Diary glimpses of university life follow, a dream collage of everyday moments, beautifully observed and filmed, precisely framed. A woman lies in bed, a man patches a wall, film students set up lights in a crumbling underground. The sound of a gathering wind marks a new chapter as the film suddenly opens up, and talks about the election of the university’s new chair Gajendra Chauhan, and the student strike response, and the familiar terror of a government aimed against its own people. The film students gather in all night meetings and marches, filling the streets with new chants.

Eisenstein, Pudovkin

We shall fight, we shall win

And then later, in a delirious montage of boy-men dancing together in their Saturday Night Fever best, their open faces not yet broken down by compromise and defeat, this heartbreaking line:

When one has loved, what is there to fear?

A keynote of Kapadia’s footage is that it was made by the people who are in the pictures, these are close encounters, insider accounts. First among equals amongst the shooters is her partner Ranabir Das. When they finished editing, Kapadia dished it all off to Lionel Kopp, a digital genius in France who added subtle layers of grain, sparkle and colour correction that made it all look like 16 mm. This powerful unifying gesture brings together the so many camera stylings together in a fine-grained, high-contrast darkness.

Kapadia’s love letter to cinema and revolution shows us a singer/guitarist at the microphone, and chooses this moment to fade out the music. As he sways to the beat, we are able to hear him in a way that only silence makes possible. His whole body is the song, and then the camera pans to deliver us to a silent drummer, carried by a tune we will never hear, until a final pan delivers us to the horn and keyboard players. By asserting their individual identities, they create a group.

Revolution is the festival of the oppressed.

In a sober display of newspaper clippings, the artist touches on “a fleeting memory of violence” — the government sanctioned war against women, Indigenous communities and Muslims. She concludes, “And each image vanished as quickly and horrifically as it appeared.” The election of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 ensured a return to “traditional values” — men over women, extractivism, religion as a ruling class weapon.

How could you stand beside me during the strike, shouting slogans of freedom, stand up to the government, but when it came to standing up to the casteism of your parents, you did not speak up?

The longest question in the film brings together the personal love story of the two letter writers, the story of their families, their school and the government. During their long and sometimes brutal strike, they are granted strength by a belief in the cinema, which is also a belief in love, and the healing transformations both might perform. Screens appear often in this lyrical essay, lit up at night where the audience are turned into shadows while onscreen actors loom larger than life. We create a life out of images, reflecting the pictures that have been passed down to us, or else we reinvent them, usually because we are forced to, because they don’t include the queer undercommons, the racialized poor, the neurodivergent immigrants. One of the many salient questions this movie poses is: how do we make a new life out of our reinventions? How can pictures help create new communities?

A brace of street demonstrations follow, the camera always part of the crowd, close enough to touch their comrades and to be touched by them. Close enough to offer a soft meditation on the policewomen, who have their own families to feed when they get home. The tender voice over raises the spectre of empathy even while her friends are being beaten and brutalized. A title interrupts these scenes of arrest with the force of a guillotine. It reads: “a souvenir of violence.”

Why can’t the poor dream of getting a degree?

This is what they are afraid of.

If we become educated, who will work on their fields?

Who will mend their shoes?

While the artist offers a lament for public education, the State sends masked goons into the university to assault students and teachers. Terrifying scenes inside schools are followed by torchlit marches. Everyone is framed by the night, so even the worst wounds appear in the flash of a camera or a passing light. The artist has combed through a wealth of crowd footage so that she can fill her frames with the inspired, articulate, outraged faces of young women. Courage made flesh.

Everything will be remembered.

One student quietly refuses to speak about his torture because he’s worried that others will be dissuaded from protest, fearing prison. What words are left in our language for the depth of this solidarity? What is clear is that the students have created a new university out of the streets, and turned each other into teachers. They practice the clumsy, inelegant form of real democracy, where everyone has a voice, and the simplest decision can take all night. How to look into these faces knowing that the man ultimately responsible will run again for Prime Minister, and be re-elected?

It’s going to be all of us someday.

India’s State machine of fog and misdirection is finely tuned, just like it is here in Canada, where so-called political reporting is careful to omit any mention of the corporatocracy that writes our laws and runs much of our country. And while we don’t have an official class of “untouchables,” our prisons are filled with Indigenous men even as the numbers of “missing” Indigenous women multiply. When I look into the gallery of Indian faces that Kapadia brings into the half-light, when I see the teenagers who have paid the price for their beliefs with a physical terror that many will never recover from, I see both a revolutionary hope and the enduring lure of tyrants that we continue to worship, obsess about, become experts on. One day I hope that we might bring that level of attention to artists like Payal Kapadia who offer new hopes for the cinema, and for us all.

|

|

« Pourquoi le cinéma ? »

Sur les spectres entre les murs

A Night of Knowing Nothing

Le plus grand spectacle au monde

Un retard

Cinéphilie et parentalité

Côté courts : mon année en moins de 30 minutes

Les temps de l'émotion

The Year of Thinking Dangerously |

|

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |