:: The Gaza Strip, photograph by ©Ismail Abu Hatab, from the series “Beyond the Sky and the Sea”

The Gaza genocide reliably delivers what Oraib Toukan names “cruel images.” There are days when Bisan Owda or Hind Rajab are closer to me than my best friend. One of them is still alive at the time of this writing. But can I say that I have witnessed Hind’s death? Toukan writes that cruel images produce silence; what can be said after seeing a boy carrying the remains of his brother in a small plastic bag who screams into the camera, “I’m only seven!” And yet the silenced body of the distant witness continues to speak, but in another voice, the voice of the trespassed, the ghost who is already dead and yet continues to bear the marks of the living.

Surely many of the images from Gaza—let us leave aside for a moment the triumphal souvenirs of the jailors—are made with the simple conviction that if “the world” could see what is happening, the killing would stop. Hundreds of millions of views, and yet the cruelty only deepens. As a result, Gaza, the political and spiritual centre of the world (in the same way that Vietnam was the centre for more than a decade in the 1960s and 1970s), seems further away than ever. Faraway so close. Is there a way of making and receiving pictures that can find a way out of this spectral labyrinth?

The beginning of every revolution is an exit. Basel al-Araj [1]

Ash Moniz is a thirtyish Canadian-born artist and activist living in Cairo and New York. Experimentalist essays on global shipping, dock workers and supply chains mark their past decade of work, that takes shape as pop-up collectives in performance, gallery installations and short films. In 2024, they met Sa’ed Al Jaru (guitar) and Siraj Shawa (keyboards) in Cairo, recent refugees from Gaza, two members of Osprey V, “the first rock band in Gaza,” and joined the band as a drummer.

Raji Al Jaru (singer, guitar): “We call it Osprey V because ‘V’ is five in Latin, which is five members, five hidden identities at the beginning, as we didn’t really want to show our faces… We wanted to be the tongues of the unheard population in Gaza Strip.” [2]

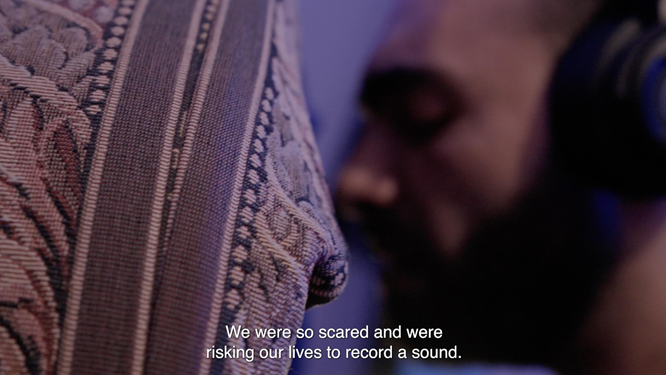

[Inaudible] by Ash Moniz+Osprey V shows the efforts of the band to make and record music as well as an accompanying video during the genocide. It is a movie made in close-up, emphasizing intimacy and touch, Gaza’s small spaces, the tight bonds of the band. Though aesthetics and fraternity were not the only reasons. In 2017, when Osprey started up, the band was always masked. They learned English and the rock music that emerged from that language, carrying hopes that international audiences would find their high-octane melancholy irresistible, though the price of these recognitions could be fatal. After October 7, 2024, most of the band fled to Cairo, while two remained in Gaza. Moamen Al Jaru, a lawyer and the band’s bass player, decided he didn’t want to risk his life by appearing in the film. Raji Al Jaru, an accountant, who sings and plays guitar, decided the risk was worth the reward. The rest of the band was filmed in Cairo as they worked on a new song, passing files back and forth to their friends back in the strip.

:: [Inaudible] (Ash Moniz, 2025)

Three band members sit in the dark watching a video in progress of their song “Mowtany” (“My Homeland”). Raji’s sweet voice longs for “Life, salvation, happiness in your love.” But alongside this ode to home, the thin buzz of a drone declares itself, louder than the music. The sound of the ruler is never far. Home is seeing friends while being seen by the state, offering promises and receiving threats, secure within the sanctuary of home, blindfolded in prison and tortured.

A key lies on the floor inside a blinking red light, surviving remnant of another stolen Palestinian home. The camera moves outside passing graffiti scrawled across ruins. “Where is my house? Where is my father? Where is my mother?” Trumpet bleats turn into the driving rock opera of the band’s newest song “Angel’s Kneel,” as we see Sa’ed sitting alone in the rubble. Pensive and anxious, the music reveals the movement in his stillness. A passing van, shot with a low drone (the tools of the master’s house can be used against him) bring us inside again, where band member Siraj Shawaplays the keys.

Raji recalls setting up the first music store in Gaza, a hub unlike any other. Every artist in the strip arrived to use electricity, Internet, sound edit software, microphones. This sound outlet gave voice to its clients, neighbourhood and community.

Band members dance in a dimly lit, misty darkness as Sa-ed’s voice-over explains, “I was unable to read normally or even act any character.” In this permanent warzone, character is an act that sometimes cannot act. How many times does one die before death? The omnipresent threats and mounting losses live in bodies that dissolve and then emerge again, speaking through phantoms. Offered in fragments, the dismembered remember.

In an unusual scene filled with everyday wonder, Raji picks slowly and occasionally at his guitar. Voice-over reflections arrive one phrase at a time. Instead of filling the frame with his portrait, the camera lingers on the bedsheets and window, the two small tables perched back-to-back, and the way the wind blows through all of it. Outside is inside. Everything is double-dutied and cramped, his bedroom is also studio, meeting room, hang out zone. The floor is a friend. “Like everyone has in Gaza,” an emergency bag waits by the door filled with official papers in case instant departures are required. The room offers us a portrait of its inhabitant and his absence. Modest and impermanent, its indigent items burnished with artful flourishes, every object touches back in a home that is not home. Like everyone in Gaza, he is in exile, and makes a temporary home here, all the more precious because of the persistent threat of new dispossessions. Somehow using only the elements of this small room, the entire catastrophe is summoned. The Nakba never ended.

Siraj names as his children: musical instruments, laptop, sound card, MIDI controller, headphones. He names them as his life.

A large photo of Gaza ruins is held up in a New York City parade, providing a canny segue into a Palestine solidarity rally. Alongside handmade protester signs to “End arms shipments to Israel,” Osprey posters appear sprinkled in the crowd. Somehow art has become politics has become art. The trumpet plays a solo version of Osprey’s “Angel’s Kneel,” which then explodes into full voice when the film switches back to Gaza and we see the band playing the tune, intercut with the faces of each member looking up into a smoky light, as if they were already in an afterlife, the nightmare of apartheid finished.

The band travels to a “studio” in Rafah (a home-made box of blankets and pillows create sound insulation for the microphone). Their destination is a tower, one of the few remaining in the strip. They record in between bomb strikes knowing the tower, like all towers in Gaza, is a target. They spend two days there, but the singer is not convinced and wants to return for more sessions. But the tower is shelled and destroyed. They miss their assassination date by a few days. Images of the Mediterranean are projected onto pillows and drapery as the voice-over narrates their “making of” story. Everything is liquid, turning and transforming. Even the sound of heaven they create in a warzone.

When shooting for the film finished, Raji was smuggled into Jordan. Moamen remains in Gaza. Ash Moniz continues to work tirelessly to support 60 people in Cairo and 40 in Gaza.

Thirty-four-year-old photojournalist and cinematographer Ismail Abu Hatab, who helped lens some of the scenes in Gaza, was murdered in July 2025, at Al-Baqa Café, a beachside joint frequented by journalists. Ismail reported for Al Jazeera and other media outlets and made lyrical portraits even during the bombings. He founded BYPA (By Palestine) to help artists in Gaza. On World Press Freedom Day 2025, he wrote, “In Gaza, the camera is targeted, the word is bombed, and the vest doesn’t protect you from missiles.” [3]

:: Ismail Abu Hatab

You can follow Ismail Abu Hatab on Instagram: www.instagram.com/ismailabuhatab/reels/

You can follow Osprey V on Instagram: www.instagram.com/ospreyvofficial

You can follow Ash Moniz on Instagram: www.instagram.com/ashmoniz

[1] Basel el-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution,” translated by Bessem Saad, in: The Bad Side, 2024, theanarchistlibrary.org/library/basel-al-araj-exiting-law-and-entering-revolution.

[2] Osprey V أوسبري:, Delia Sessions #015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoUkqoIvVGY&list=RDeoUkqoIvVGY&start

_radio=1&ab_channel=DeliaArtsFoundation.

[3] Quoted in: “Between sky and sea this was where martyr journalist Ismail Abu Hatab opened a window to Gaza,” The Palestinian Information Center, July 3, 2025, english.palinfo.com/Zionist-Terrorism/2025/07/03/342494/.

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |