Whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice— Louise Gluck, The Wild Iris

I had never met a journalist who made artist movies before. It was rare enough that Annie Sakkab was splitting her time between Jordan, where she was born, and Toronto, her newly adopted city. Though she didn’t call it Jordan, she called it Palestine. Canada held the promise of a second life, one she was supposed to enter with her beloved, freed at last from the religious restrictions back home. But cancer found him first, even as a young man, and she watched him die, and with him, every dream of who she was, and who they might become together. So when she came to Canada, it was not the fulfilment of a dream, but a flight from a life that had been taken away from her. For a few years, she struggled to hold, to contain, what cannot be held. And then she reinvented herself at school as a photo journalist. After speaking with Alia Hogben, then Executive Director of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women, she had an epiphany, and decided to dedicate her work and life to women’s stories.

She interned for a couple of Canadian newspapers, then took a Globe and Mail assignment to photograph Syrian refugees bound for Canada. This led to a work invite from the United Nations, both photographing and videotaping Syrian refugees, at first in Jordan, and then across Canada, as they settled into new homes and communities. But even as she was making her way as a journalist, she could feel the tugs of deeper conscience. While her UN gigs gave voice to the voiceless, it was ultimately aimed at raising funds for the agency, so a relentless positivity infected the practice. What she needed was to dig back into situations where she could offer pictures that would ask questions, inviting viewers into the mess and complication of real lives.

Her first independent film was Hollie’s Dress (25 minutes, 2020). It is part of a six-year project called Keepers of the Home (2016-present) that looks at a Mennonite family in southern Ontario. Mennonites remain a fairly closed religious community, with strictly defined roles for men and women. Boys are expected to become farmers and provide for their family, while girls have the choice of pursuing education and a career or to marry and raise children. Hollie spent her childhood sewing heartbreakingly beautiful tops and pants for her dolls. Good practice for future sewing duties, no doubt. Girls receive their last doll when they are 12.

Hollie wears a quiet smile on her shy face throughout the film. It is a smile that looks inwards, as if she has just accomplished a self-examination and found everything in order. She was just 12 when the project started, while filming began during a period when this teenager would have to make a choice that would direct the rest of her life. The challenge for the artist was how to deliver to the viewer the feeling that this was a real choice, to allow us to enter into this world without judgment. The artist dug into her own past for clues, questioning the choices girls back in Jordan had in a distinctly patriarchal society where forced marriage still begins as early as 13, and men can have up to four wives. Every picture the artist makes touches this place in her own past, allowing her to create frames of empathy and benevolence. These deep roots set her images apart. Filmed in luminous high-key settings, Annie shows up day after day, finding small moments of mother-daughter communion as traditional knowledge is passed down. Her tender camera approaches Hollie and her mother with respect, and slowly allows us to enter their worlds of singing together, buying fabric, and most centrally, making Hollie’s first dress.

*

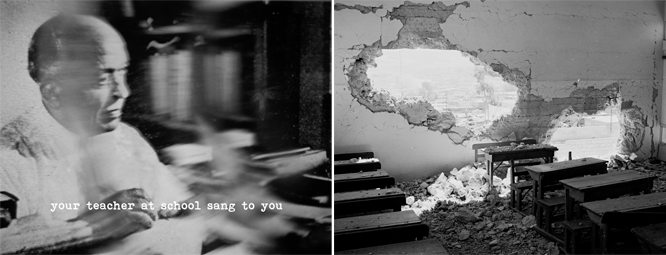

For her latest movie, The Poem We Sang (20 minutes, 2023), Annie returns to her own childhood in Palestine. Because the project began during COVID lockdowns, she was unable to shoot or even visit home. She decided she would take a more experimental approach, asking a question that continues to haunt Palestinian artists: How to make a picture of what is no longer there?

The centrepiece of the film, its anchor and closing scene, is a poem by the legendary Palestinian writer and educator Khalil al-Sakakini. He brought radical reforms to education, did away with competition and awards, taught Arabic using mime and theatre, and established a school in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1948, Israeli shelling closed the an-Nahda College and drove him out of his Jerusalem home and into Egypt, where he resettled. His voluminous library was stolen by the Hebrew University.

Khalil al-Sakakini schooled both Sakkab’s father and uncle, and they learned many poems from him “by heart,” as the saying goes; their spontaneous recitals became a cornerstone of the artist’s childhood. Her lockdown task was to find a way to give this poem a shape, using only found footage. She worked for many months, finally producing a short, dense, multi-screen exploration that centred on her uncle’s letters and the bridge that linked the large exiled Palestinian population in Jordan to Jerusalem.

The Al-Karameh Bridge is a site of national wounding. For decades, Palestinians underwent excruciating and invasive security procedures by Israeli authorities, standing for hours before undergoing forced nudity and theft of personal belongings—a routinized state-sanctioned humiliation. While this is not explicitly shown in the film, for Palestinians in the region, the site of the bridge is enough to recall both the promise of Jerusalem, and the cost of arrival. It is one of many moments in the film where meanings shift depending on the backgrounds of the viewers.

Annie opens her movie with a fairy tale, a hand-drawn animation of a young girl crossing the bridge freely as butterflies float by. An older woman opens a drape, but what she looks out on are newsreel images of the past, a wedding procession, fleeting figures drifting across the landscape of memory. A young girl opens a letter from her uncle Elias, a poetic embrace assuring her of her genius and his love. She answers in a quick collage of family photos, glimpses of Jerusalem, a woman washing dishes, a group of young girls dancing, before canons fire and war erupts. The Nakba begins. Territory is claimed by armed Jewish groups, Palestinians are thrown out of their homes, a man reads out their names as they clamber aboard buses that will take them to safety, and condemn them to a permanent exile.

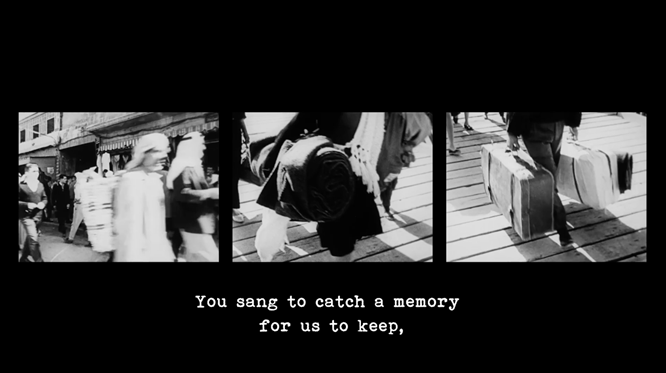

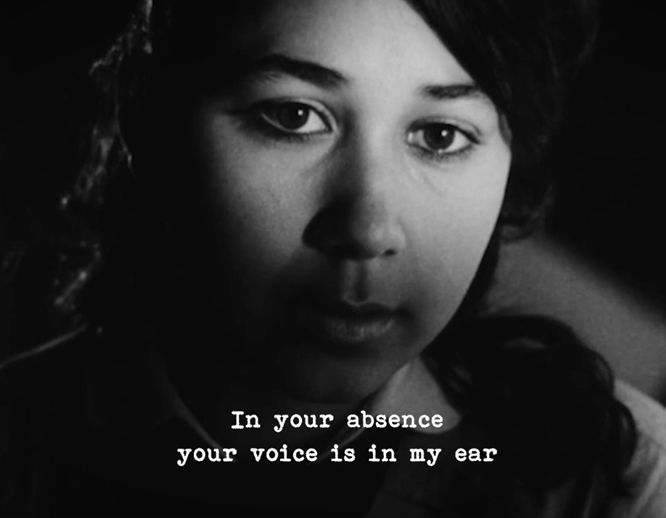

The rest of the movie is driven by the filmmaker’s voice over, a poetic letter to her family, filled with the youthful hopes of a girl and her longed-for country that is also her childhood, and the childhoods of her ancestors. Annie pictures a stand-in for herself, shot in Bethlehem, a pensive girl turning in the long grass or wandering the crowded streets, offering worried looks into a newly threatening horizon. The movements are slowed, close-up and graceful. A white butterfly vanishes, and then her uncle vanishes from his hospital bed, it seems she put off visiting him until it was too late. These ghosts are part of the disappearance of an entire country.

My father left Palestine for the last time in 1967 and took with him the only thing he was able to keep, the same song for us to sing, for us to repeat.

We see an image of a father crossing the wooden bridge into Jordan, carrying a child in his arms. A hand opens and jasmine flower petals fall into the opening palm—it’s a trick shot, using reverse motion. Granules of soil fall back into the hands that released them. As if exile could be reversed, or that a state might arise without ethnic cleansing. Newsreel footage shows families at home, laughing and eating, and then soldiers kicking down their doors, bulldozers tearing down small apartment blocks. Until these pictures too are reversed. Soldiers run backwards. Bombs unexplode. Palestinian boys unthrow stones.

I’m going to work for getting back my country.

A young woman speaks calmly into a British news camera. Thrown out of her home in Palestine, she has become an exile in Egypt. Who is allowed to be a citizen? Who is a person and who is not? Like many states, Israel begins with an act of drawing borders that decides who will be fully human, and who will not.

Cleverly using her newsreel footage as a kind of script, the artist shoots present-day cutaways and movements with her young stand-in, so that Annie can cut back and forth between the two. Street crowds and vendors from the present look out onto crowds from the past.

The camera is a haptic device, offering us a touch that brings these faraway Jerusalem scenes close. We can feel the crease of each almond, the girl’s windblown hair, even the photographs that appear are often shot through glass, or a present-day reflection that turns them into something uncanny and alive. A girl and boy crack almonds on a sun-drenched step, shells gathering below them. And then the separation barrier appears, scribbled and scratched over, an image of state power and individual protest. The reverie of a shared childhood moment is over.

Annie returns to the bridge, where her grandparents are leaving home, imagining they will return in a week, not knowing that they will never see home again. Once again, she uses a canny blend of present-day shooting and archive footage that she shows both full frame and in a triple-screen array, suddenly multiplying the view, offering simultaneous vantages on the same bridge crossing, the same war.

We do not mind giving our lives

For us to reach our destiny

This land that we have inherited

The last minute-and-a-half of the movie is given over to Khalil al-Sakakini’s poem. The artist sings it in a strong voice filled with an uplifting brightness. Onscreen, landscapes drift past, verdant treetops sway, signs point the way to Jerusalem. The young girl watches from a sun-drenched backseat until at last the car enters the capital.

When I interviewed the artist in the fall of 2022, she announced she would be leaving Canada and taking up permanent residence again in Palestine. She wanted to tell the stories of Palestinians, because they are not seen as humans. She cited the routine imprisonment of children, the daily murder of civilians, the starvation diets and lack of medical supplies, the humiliations and terror, all a decades-long commonplace. How bracing it is to see these urgencies taken up by an artist of such sensitivity and with such deft material handlings. Her ability to stand in the most difficult places in her own life has created strong foundations for a practice that continues to inspire.

Color pictures : Hollie's Dress, 2020.

B&W pictures : The Poem We Sang, 2023.

All the pictures : B707 Productions.

*

Mike Hoolboom began making movies in 1980. Making as practice, a daily application. Ongoing remixology. Since 2000 there has been a steady drip of found footage bio docs. The animating question of community: how can I help you? Interviews with media artists for 3 decades. Monographs and books, written, edited, co-edited. Local ecologies. Volunteerism. Opening the door.

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |